DEMOGRAPHICS:

Naples is located in the capital of the Campania region and the metropolitan city of the same name, the centre of one of Europe’s most populous and densely populated metropolitan areas; is also the most populous municipality in southern Italy, Italy’s third largest country by population (after Rome and Milan), the largest municipality by density of population and one of the twenty most populous cities in the European Union.

In the municipality of Naples, the resident population, which consists of people with usual residence in the same municipality, is 1,004,500.

The relative presence of children is above average national. In particular, in the municipality of Naples the percentage of children under five years old is 5.29%, higher than the 4.59% recorded at national level.

Unlike the national situation, the definitive data from the 2001 Census on the demographic structure of the population reveals a demographically young municipality. The percentage ratio between the population aged 65 and over and those under 15, known as the old-age dependency ratio, is less than 100, indicating a lower level of population aging. In fact, in the municipality of Naples, it is 91.13%, which is lower than the national figure (131.4%).

Another indicator, with economic and social relevance, is the dependency ratio, also known as the demographic dependency ratio. This ratio compares individuals who are presumed to be non-autonomous due to demographic reasons (age)—namely the elderly and the very young—with those who are expected to support them through their activities. In the municipality of Naples, the ratio, which stands at 48.58%, is lower than the national figure (in Italy, 49.02%).

The reference to the land area occupied by the population (117.27 square kilometers) allows for the calculation of an indicator, the population density, which has a value of 8,566 inhabitants per square kilometer. This figure is excessively high, especially in comparison to the national data (189 inhabitants per square kilometer).

CULTURE:

A city with an impressive tradition in the visual arts, rooted in classical times, has given rise to original architectural and painting movements, such as the Neapolitan Renaissance and Neapolitan Baroque, Caravaggism, the Posillipo School, the Resìna School, and Neapolitan Liberty. It is also known for lesser arts of international significance, such as Capodimonte porcelain and the Neapolitan nativity scene.

It is the origin of a distinctive form of theater, a world-famous song, and a unique culinary tradition that includes foods that have become global icons, such as Neapolitan pizza and the art of its pizzaioli, which has been recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

In 1995, 10.21 square kilometers of the historic center of Naples were recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage site for their buildings and monuments, which testify to approximately three thousand years of history. In 1997, the Somma-Vesuvius volcanic system was designated by the same international agency (along with the nearby Miglio d’oro, which also includes the eastern neighborhoods of the city) as a World Biosphere Reserve.

In Naples, traditions are rich in secrets and nuances, which is why they have been passed down orally from generation to generation for a long time. Indeed, the elderly have become the means through which we can trace back to the traditions of the past: recipes, sayings, board games, Neapolitan songs, jokes, and more.

THE PIZZA A PORTAFOGLIO: Pizza, an undisputed symbol of Naples, is often enjoyed ‘a portafoglio.’ This tradition arises from the need to eat quickly, perhaps while walking through the streets of the city. The pizza is folded over itself several times, forming a kind of wallet, making it easy to eat with one hand.

BOLOGNESE: Ragù is truly a philosophy in Naples and reflects a sacred principle in its culture: conviviality. The warm hearth of home and family Sundays enrich this sentiment. Tradition dictates that the preparation of Ragù begins on Saturday evening, and even today, despite technology allowing for quicker cooking times, there are still those who maintain what many consider a true ritual that elevates the essence of ‘being together.’ It’s nice to think that, even now, the tradition is still alive, and despite the logistical shortening of cooking times, a nostalgic Neapolitan is always willing to rise early to prepare a succulent Ragù. The methods have remained the same for over a century: long cooking and very low heat. On the stove, stirring with a spoon to prevent the mixture from sticking to the bottom of the clay pot, the sauce thickens, the meat becomes tender, and absorbs all the flavor of the tomato. But the crucial phase is that it ‘adda pippià (‘it has to simmer’). The cuts of meat used vary from family to family. Generally, the most common are beef, pork, or veal; often, braciole are added, stuffed with various ingredients such as raisins, pine nuts, salami, lard, grated cheese, garlic, and parsley. Sometimes, pork rind and meatballs are added to the sauce, but only after being fried.

SPAGHETTI WITH CLAMS: This is one of the iconic dishes of Neapolitan cuisine, traditionally served at the beginning of the Christmas and New Year’s Eve feasts. Although it is a dish that requires few and simple ingredients, its successful preparation is anything but guaranteed. Spaghetti with clams is made by sautéing garlic in a pan with oil, then adding the clams, which will cook for 2 to 3 minutes until fully opened.

PASTIERA: This is a sweet dish from Neapolitan cuisine, typical of the Easter period and widespread throughout Campania. Also known as wheat pie, the dessert, according to legend, was created by the siren Partenope herself and likely originates from pagan festivities and votive offerings of the spring season.

SFOGLIATELLA: This is a typical sweet from Campanian pastry, available in two main variations: it can be ‘riccia’ if made with puff pastry, or ‘frolla’ if made with shortcrust pastry. The sfogliatella originated in the 18th century at the Santa Rosa da Lima convent in Conca dei Marini, almost by chance: some semolina dough had been left over in the convent’s kitchen; instead of throwing it away, dried fruit, sugar, and limoncello were added to create a filling. In 1818, Pasquale Pintauro, a Neapolitan pastry chef, acquired the secret recipe of the Santarosa, bringing the sweet to Naples, making some modifications to the recipe that is still used today, and introducing the shortcrust variant.

SOSPENDED COFFEE: This is one of the most beautiful and meaningful traditions of Naples. When a customer feels particularly fortunate or wants to make a gesture of generosity, they can pay for a ‘suspended coffee.’ This means they have paid in advance for a coffee for the next customer who cannot afford it. It’s a small gesture of solidarity that demonstrates the great spirit of the city.

THE TARANTELLA: The tarantella is a traditional Neapolitan dance, often associated with festivities and celebrations. Characterized by fast movements and lively rhythms, it represents the vibrancy and passion of the Neapolitan people.

THE NATIVITY SCENES: During the Christmas season, the streets of Naples come alive with the tradition of nativity scenes. Via San Gregorio Armeno is particularly famous for its artisans who create detailed figures and intricate settings, representing both religious scenes and moments of everyday life.

THE FEAST OF SAN GENNARO: Every year, on September 19th, the people of Naples gather to celebrate San Gennaro, the patron saint of the city. Tradition holds that the blood of the saint, preserved in two ampoules, liquefies in the presence of the faithful, bringing good fortune to the city for the coming year.

RUM BABÀ: This soft, rum-soaked cake is a must-try for anyone visiting Naples. With its distinctive shape and unmistakable flavor, the babà represents the sweetness and generosity of Neapolitan cuisine.

RELIGION IN NAPLES: In a city that lies next to a dormant volcano, the sense of miracle is a daily experience. A popular and participatory faith animates the churches during every religious occasion. But seeking good fortune and warding off bad luck are activities taken very seriously by Neapolitans, under the motto: ‘It’s not true, but I believe it.’ When walking through the historic center of Naples, lucky charms alternate with busts of San Gennaro, just as Pulcinella masks alternate with the skulls of the Souls in Purgatory. Neapolitans are Catholics, but in their own way, a wholly pagan manner, a legacy of those Greek roots that quietly survive in the collective unconscious. In the streets of ancient Neapolis, religion and superstition intertwine; faith and folklore speak a single language that reflects a distinctly Neapolitan logic. In the alleys eroded by time and humidity, elderly ladies who have images of the Madonna or Saint Anthony hanging on their walls greet Bella ‘Mbriana, a benevolent spirit from popular tradition who watches over the home and, if she takes a liking to us, ensures good fortune for life. At Bar Nilo on Spaccanapoli, the owner has set up an altar displaying a ‘relic’ of Maradona, because in Naples, relics are not just those of saints, as tradition would suggest; to avoid offending anyone, this particular relic, made from a lock of hair from the most beloved player in the city’s history, is surrounded by sacred images. Above them all stands Pope Francis, flanked by not one but two busts of the patron saint, San Gennaro, followed by the Madonna of Pompeii and Saint Giuseppe Moscati, one of the more recent Neapolitan saints. The Greek pragmatism remains in Naples in the familiar way people speak to the saints. In church, it’s common to see the faithful take a saint’s hand and begin to whisper requests about what is most important to them, sharing their troubles in a colloquial manner as if speaking to a dear person, someone at their level, someone they trust, who listens benevolently. All this is because, in Naples, saints are not superior beings, unreachable… they are people like us, to be touched, with hands or words. The cornicello, which you often confuse with a red pepper, is the Neapolitan good luck charm. The Neapolitan cornicello is the miniature version of the cornucopia so cherished in the pagan world, a bull’s horn that, in the Middle Ages, was dyed red to symbolize victory over enemies. The most powerful horns are said to be made of coral, as the Romans believed coral was a catalyst for positive energies that protects us from the envy of others. Every Neapolitan has received at least one as a gift.

THE NEAPOLITAN LANGUAGE

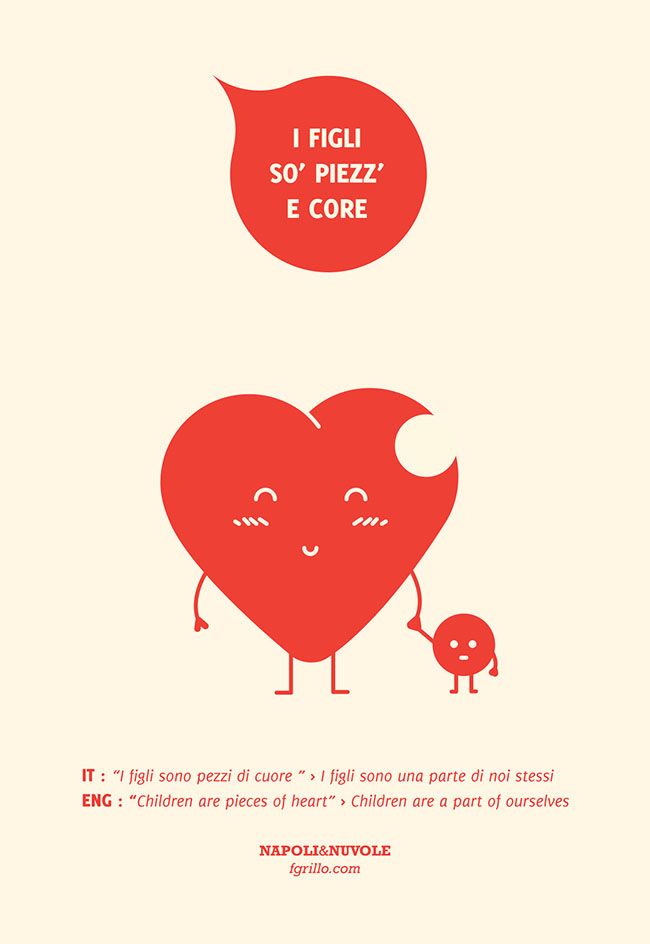

Neapolitan is a language (not a dialect) that is not only musical but also particularly rich in imagery. “‘O core dint ‘o zucchero” (‘the heart in the sugar’), “i figli so’ piezz ‘e core” (‘the children are pieces of the heart’), “‘a Maronna t’accumpagna” (‘the Madonna accompanies you’): figures dense with meaning and charm in their simplicity.

A unique aspect of these particular idiomatic expressions is how their endurance over time has added a playful touch to their semantic value, especially when imagining them in tune with the times.

It reflects the work of Neapolitan designer Francesca Grillo, who, now based in Rome, has depicted some of the most fascinating expressions of the Neapolitan language through playful images in ‘Napoli & Nuvole’.

With a simple style and accompanied by explanations in English, the designer not only does justice to the expressions but also gives them and their genuine Neapolitan essence a well-deserved potentially international showcase.

TO BETTER UNDERSTAND NEAPOLITAN CULTURE, WE ATTACH A STORY: https://italianosemplicemente.com/archives/66576